About Nellie Mae Rowe: In Her Own Words

Judith Alexander interviewed Nellie Mae Rowe in 1982, shortly before the artist's death. She compiled the following excerpts from those tapes which have long since disappeared.

Nellie Mae Rowe (detail), 1971, © Judith Alexander Augustine

Used with permission

I was born July 4, 1900, and raised on my parent’s farm in Fayette County, Georgia.

When I was a little girl I would lay down on the floor and get my pencil and draw. I would draw all different things and after I finished drawing I would go in the kitchen and steal some flour, make it up into dough, and stick the drawings up on the wall. My sister would say. “Mama, make Nellie quit putting those drawings up”, but Mama would let me go on doing it.

I didn’t go to school to learn drawing. I guessed at it when I was a little gal. Because we had to go to the fields, pick cotton and all like that, I didn’t have a chance to draw like I do now, and every chance I had, I would get my pencil, get down on the floor and draw until they said, “Nellie, let’s go.” At night I would get through with everything, get ready for bed, get my pencil and draw something. That was just in me and it is still in me. I would draw whatever I thought of, just like I do now.

I bet I wasn’t 10 years old when I made my first doll. Sometimes when I ought to have been in the fields, I’d hide and go make dolls. I’d take up all the dirty clothes, tie them up, pack their heads full of soft stockings, and make eyes for them. I made some to look like people, but I would not tell them because it might hurt their feelings. They might not like the way they looked. When I was at home I was always studying about tying my clothes up. When Monday morning washday came, the clothes would be all tied up in knots, eyes anywhere I had used the pencil. I had to sit down and untie these clothes so I could wash them.

There were nine girls and ten with the boy. The older ones were married and had children when I was coming up. I was second from the youngest. (Now there are two of us, my sister Minerva Brown and me.) Four of us came up together: Eva, May, Willie, and me. Eva liked to make dresses; May liked to cook; and Willie, the youngest, was just like me—she liked to play with dolls. Willie couldn’t make dolls like I could, so I made hers, too. We would get the clothes all tied up, sweep out from under some little pine trees and make the prettiest playhouse. I would hate it when our mother called us to the house because I wanted to be playing in my playhouse.

My mother was born the year of freedom. She always said that she was born the year they freed the blacks. She wore silver dimes around her arms for rheumatism. She knew all kinds of remedies. We would go to the woods and pick sorrel grass and catnip and such. Now we go to the doctor because we don’t use herbs the way Mama did. My sister, Minerva, uses her own herbs. She won’t go to a doctor. She still works every day and is ninety-four years old.

My Mama did everything. She was busy all the time; she made quilts and taught me to make them. I loved to quilt because it kept me out of the field, out of the sun, and in the shade. Mama made our dresses. At Easter time Daddy would buy a bolt of cloth. We didn’t want the dresses alike, but we could get the cloth cheaper that way. Mama made them all different. Daddy bought us white high boot shoes and white stockings. God bless your soul, we thought we were dressed!

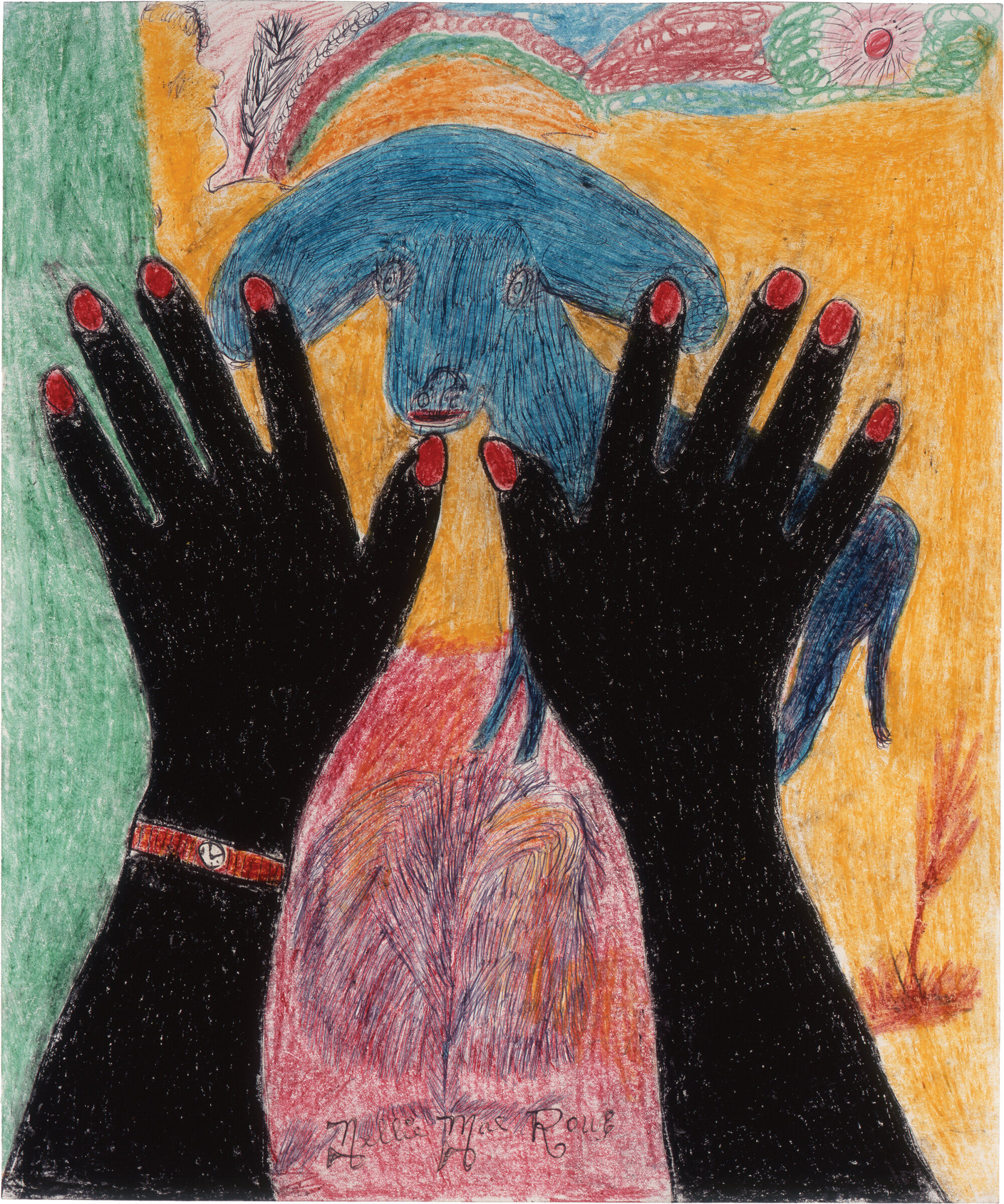

Untitled (Peace) 1978-1982 Gift of Judith Alexander © Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe, High Museum of Art Atlanta

Thank the Lord we are here now because I couldn’t go through what my Mama went through being as smart as she was, waiting on all those children and grandchildren. She stayed home and cooked and was satisfied. I know she got tired being at home. The cotton fields were right around the house and she would get her sack in her little spare time, get out there and pick an old sack full; she just wanted to be doing something. She got tired cooking; I know she did. She had everything to do. We picked the greens and carried them home, but she had to do all the washing of the greens.

We had to go back to the fields and sometimes we would get wet clear up to the knees. We could not afford to wait until the grass and cotton dried off in the field, because it would take up so much of the day. Then we worked from sun-up to sun-down, sun-up to sun-down, but we were working for ourselves.

I favored my daddy more than my mother. I’m short like him, but not as smart. He knew how to do most anything. He made the finest baskets in Fayette County. People came from all over to buy them. He was a farmer and a blacksmith. He had a syrup mill. He would hitch the mule to the mill and the mule would go-’round and ’round grinding the juice out of the sugar cane. Then he strained and cooked it. That was the best syrup you could eat; people liked to buy it.

We had our own sweet potatoes, corn, Irish potatoes, beans and peas. We shelled the peas and put them up, cut the beans and canned them. We always had meat, slices of ham, and sometimes hog shoulder, and we had all the milk and eggs we wanted.

Daddy was a smart worker and he kept us in the field doing all kinds of work: picking cotton, chopping cotton, hauling corn and watermelons. We had a big apple orchard and we would haul the apples to the barn. We plowed with the mules, Molly and Mike. I plowed with Molly; I plowed with Mike. I talk about it, but I didn’t like to plow. I didn’t like to do anything in the field. I also fished, but I didn’t like to fish.

I just liked to draw and make dolls.

My daddy lived in slavery times. He would sit down at night and tell us children, “You all think you are having a hard time, you ought to have come up when I did.” He said, “Just like you get a bucket and go out there and feed my hogs in the trough, that’s the way I was fed coming up in slavery times.” He was just saying we ought to be grateful that we didn’t come up like he did.

I have no energy to draw pictures about slavery times. It makes me feel sad. You must not think back to those times because these are new days.

That is why I don’t like to look at ROOTS. It makes me feel like I was back in slavery times. You see one and then another being whipped until the blood comes out and I don’t want to look at it. I think to myself, “If I’d been living then it would have been my skin.” In ROOTS you see them plowing the field, barefoot with some old swamp hat on, and they look back and the boss maybe looking at them . . . Oh, Lordy! Lord have mercy. That seems pitiful, seems mean and pitiful.

I was about seventeen years old when I ran off and got married. If I had stayed home I would have been better off. I’ve been married twice. The first time we stayed around Fayette County where I was born until we moved to Vinings in 1930. He farmed and worked the sawmill awhile. He died in Vinings in 1936. Later that year I married Henry Rowe who was much older than me. We built this house in 1939, and we lived a good little life here. He farmed and I worked for the Buddy Smiths in their home across the road for the next thirty years. I didn’t start back drawing when I was working for them, no more than maybe just sit down and draw something and throw it away. I would just pick up some big brown piece of paper and draw a great big picture on it.

I didn’t hang anything outside or draw while Henry Rowe was alive. When he died in 1948, I started hanging things in the yard, in the trees and bushes. I said, “Now I’m going to get back to when I was a little gal playing in the yard, playing in my playhouse.”

Detail inside Nellie’s Playhouse 1971 © Judith Alexander Augustine Used with permission

The yard was decorated pretty. Because of the talent God gave me, many people started visiting and taking pictures. What is exciting and surprising and makes me feel good is to think about the people I would never have seen if I had not been doing things that were interesting to them. Folks brought me all kinds of things: dolls, stuffed animals, beads, bottles, and sometimes strangers would leave things at my gate. I would place them in my yard and some I would hang indoors against the walls. Everything else, other than what people gave me, I picked up. I like it when things keep on changing; keeps me busy.

I chewed a lot of chewing gum because the doctor said chewing would help the jumping in my head. People began bringing me packages of chewing gum. And I said, now as much chewing gum as I chew, I’m going to make something. So I saved my chewing gum and when I saved a big ball, I started making things. I used to have chewing gum cats and dogs all up and down my fence. Now, I chew gum just to make things.

When other people have something they don’t know what to do with, they throw it away, but not me. I’m going to make something out of it. Ever since I was a child, I’ve been that way. I would take nothing and make something.

Long time ago people were very mean to me. Because I kept things hanging in the trees and bushes, they thought I was a fortune-teller. They knocked all my windows out. They threw rocks, firecrackers, old rotten eggs, and everything up against the house. Some of them said I wouldn’t stay in the house. But I kept on tolerating them and talking to the Master until they stopped. If you trust in God all will be well. I stayed on here and I’m still here.

In my home, there were nine girls, and I was the only one who didn’t have children . . . but He gave me this gift. He is the One who gave me this hand. As I tell it, God gives everybody a talent. It was my talent to lay down on the floor and draw. Don’t you know the Lord is good to us when we don’t know He is good to us? I know He is good to me because He leads me and guides me and I have to draw the way my talent that God gave me tells me what to.

I draw what’s on my mind. What’s important is thinking about what I’m going to make. I sit and look my paper over. It will come to me. I look and study and if I see a man’s head, a woman’s head, a woman’s feet, or anything, I start from that. I may make a start with a straight mark, and it will come to me what I want to make. And also if I’m going to draw a tree, I wouldn’t know what kind it’s going to be until I get started. Then it may turn out to be different from what I started it to be. I just guess at what I do; it just comes in my mind.

When I draw I first take a common pencil, and if I draw an eye that I don’t like, I can spoil it out. Then I use my colors. I don’t care if the color is ink, watercolor, crayon, or pencil, whatever matches is what I will use. What paper takes the best is the one I will use.

When I went to New York in the airplane, I saw a picture in the clouds and I got my pencil right out. I drew something with a long tail and horns.

I can draw roses real good. I don’t have to look at them. I just know how roses grow, how vines and trees grow.

I just draw the way I see things. I see people crippled and I may draw them to ask the Lord to help them. Nothing I draw I draw to make fun of. I draw what I see of people’s condition and I ask the Lord to help them.

I don’t know why He put me here but He has me here for something because I don’t draw like anyone else; I don’t try to draw like anyone else. I see what I draw in my mind late at night and I don’t care how crazy it is, I’ll probably draw it.

Nellie Mae Rowe, Vinings, Georgia (detail), 1971 © Melinda Blauvelt

Things come to me in my sleep and sometimes I will get up in the night and make a start of what I’ve seen. If I don’t I will forget how it looked the next morning. It is just like a dream to me when I see those things. Most of the things that I draw, I don’t know what they are by name. People say, “Nellie, what is that?” I say I don’t know, it is what it is. That is all I know. But I know one thing, I draw what is in my mind. I draw things you haven’t seen born into this world, but these things may someday be born but I’ll be on through.

The pictures I am proud of that I have made are of my hand. I leave my hand, just like you leave your hand on the wall. I leave my hand on the wall. When I’m gone they can see a print of my hand. I love that—to see a print of my hand. I’ll be gone to rest, but they can look back and say “that is Nellie Mae’s hand.”

I enjoy trying to draw when I am sick. I just have to be doing something. Drawing is the only thing I think is good for the Lord. I try to draw because He is wonderful to me. I just have to keep drawing until He says, “Well done, Nellie, you have been faithful.” Then I will know that I have finished my work. When I wake up in glory I want to hear “Well done, Nellie, well done.” That is when the happiness come by.

All my dolls, chewing gum sculptures, everything will be something to remember Nellie. If you will remember me I will be glad and happy to know that people have something to remember me by when I’m gone to rest.

I’m so thankful I’m able to be up in my sick days. I feel like I’m growing stronger because I’m serving the Lord, and I thank Him for everything; letting me stay here this long, living down here on love and land, for this world is not my home. My home is on high and I’m going to reach it one day. (I have to take time and get my breath. I’m growing short-winded.)

I like to do my work; I enjoy sitting here drawing. As long as I’m able that is what I’m going to do. When I was a child, I always liked to get a pencil and paper, get down on the floor and draw. It didn’t amount to nothing then, but in the long run, it did. You first have to be a baby, then you go crawling, then you walk. So I kept on moving along until I got to be an old woman. Now I got to get back to my childhood, what you call playing in a playhouse. My little old house is just a playhouse, just something to sleep in like it was when I was a child. I love to have a playhouse. I use to keep it up better, but I’m kind of weak now, but I can keep it up good enough for you to come visit me. You all come and see me anytime, be glad for you to come by to see me.